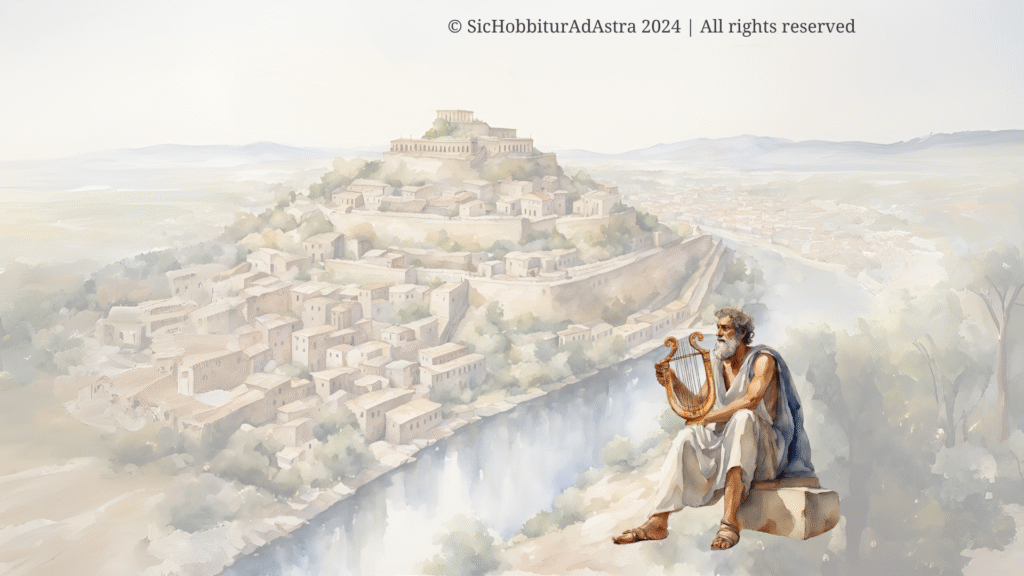

Greek mythology offers a powerful lens through which students can explore enduring questions of justice, belief, and sacrifice. The sacrifice of Iphigenia—as told by Homer and later reinterpreted by Lucretius—confronts us with a troubling scenario: can religion ever justify the death of a daughter? This ancient dilemma remains startlingly relevant today, especially considering that religious wars and conflicts continue to cause profound suffering around the world.

A Complex Figure in Classical Literature

When the Greek fleet is stranded at Aulis due to calm winds, the seer Calchas declares that the goddess Artemis is angry. To appease her, King Agamemnon must offer his daughter Iphigenia as a sacrifice. To appease her, King Agamemnon must sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia. He is torn. Refusing would mean abandoning the Trojan War and bringing shame on himself and his army; accepting would mean killing his own child. In the end, he gives in. Iphigenia is summoned under false pretenses—she is told she will marry Achilles—and, depending on the version of the myth, she is either sacrificed or saved by the goddess.

Over time, Iphigenia has become a symbol of innocence sacrificed for a supposed greater good. In ancient Greek culture, Agamemnon’s act might have been viewed either as obedience to the gods or as a tragic moral failure. The myth itself presents varied and sometimes conflicting versions: sometimes Iphigenia dies, sometimes she is saved; sometimes she resists, other times she accepts her fate.

But it is in the work of Lucretius, a Roman poet and philosopher of the 1st century BCE, that the story takes on a sharper tone.

Tantum religio potuit suadere malorum (De Rerum Natura, book 1)

“So great the evils that religion could persuade.”

For Lucretius, the sacrifice is not a pious act, but a horrifying result of superstition. Drawing from Epicurean philosophy, he denounces fear-based religion and promotes rational understanding as the path to peace.

Two Texts, Two Visions of the Sacred

In Homer’s world, religion is part of the natural order. The gods are not moral exemplars, but powerful forces who must be respected through ritual and sacrifice. What is right in this worldview is often about preserving cosmic and social balance, not about justice as we understand it today. Agamemnon does not want to kill his daughter—yet within his worldview, he believes he must. His actions are tragic because they are humanly comprehensible.

Lucretius, by contrast, offers a rational, secular perspective. For him, religion is a source of fear and suffering. Iphigenia’s death is not a divine necessity but an irrational horror. Lucretius’s telling warns against surrendering moral judgment in the name of supernatural authority.

These contrasting approaches allow students to explore major themes in classical literature and philosophy: the role of religion in society, the tension between duty and morality, and the human cost of belief systems. They also create a bridge to modern ethical debates.

An Open Question for the Classroom

The sacrifice of Iphigenia compels us to ask: how far can we go in justifying violence in the name of faith? What separates true belief from blind superstition? And can reason and reverence truly coexist?

These are not easy questions—but they are precisely the kinds of questions that high school students are ready to explore. Presenting these ancient texts side by side opens the door to critical reading, ethical reflection, and rich classroom discussion.

A Ready-to-Use Resource for Comparison and Analysis

This is the spirit behind our latest high school resource, which compares the sacrifice of Iphigenia as depicted in both The Iliad and De Rerum Natura.

Perfect for literature, philosophy, or world history classes, this digital activity includes:

- adapted excerpts from Homer and Lucretius;

- a clear side-by-side layout for close reading;

- guiding questions for textual analysis;

- an argumentative writing prompt to help students form and support their own position.

Use it as a short unit on Greek and Roman thought, a supplement to your mythology curriculum, or a bridge to contemporary ethical discussions.

Thank you for reading! As always, the work we do in the classroom is also a quiet dialogue with what endures—and what returns. The myths still speak, if we are willing to listen.

Until next time,

Chiara